Introductory statement “Financial stability in uncertain times: the Bundesbank’s Financial Stability Review 2025”

Check against delivery.

- 1 Macro-financial environment: challenges and risks

- 2 Rising government debt: risks to financial stability

- 3 Credit and assets: state of the financial cycle

- 4 State of the financial system: the situation for banks

- 5 NBFIs: growing importance and systemic risks from interconnectedness

- 6 Resilience: final assessment and implications for macroprudential policy

- 7 Concluding remarks

Ladies and gentlemen,

Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.

This quip by Danish physicist Niels Bohr perfectly sums up the starting point from which we produced the twentieth edition of the Bundesbank’s Financial Stability Review.

Exactly one year ago today, on the morning of 6 November 2024, the outcome of the US presidential election had become clear. Since then, a lot has changed and the world has become more uncertain. We, too, had to revise some of our previous assessments on the state of economic activity and the macro-financial environment. In addition to the US elections, this is also related to the rising geopolitical tensions over recent years. At the same time, structural challenges are weighing on the German corporate sector to an increasing degree.

1 Macro-financial environment: challenges and risks

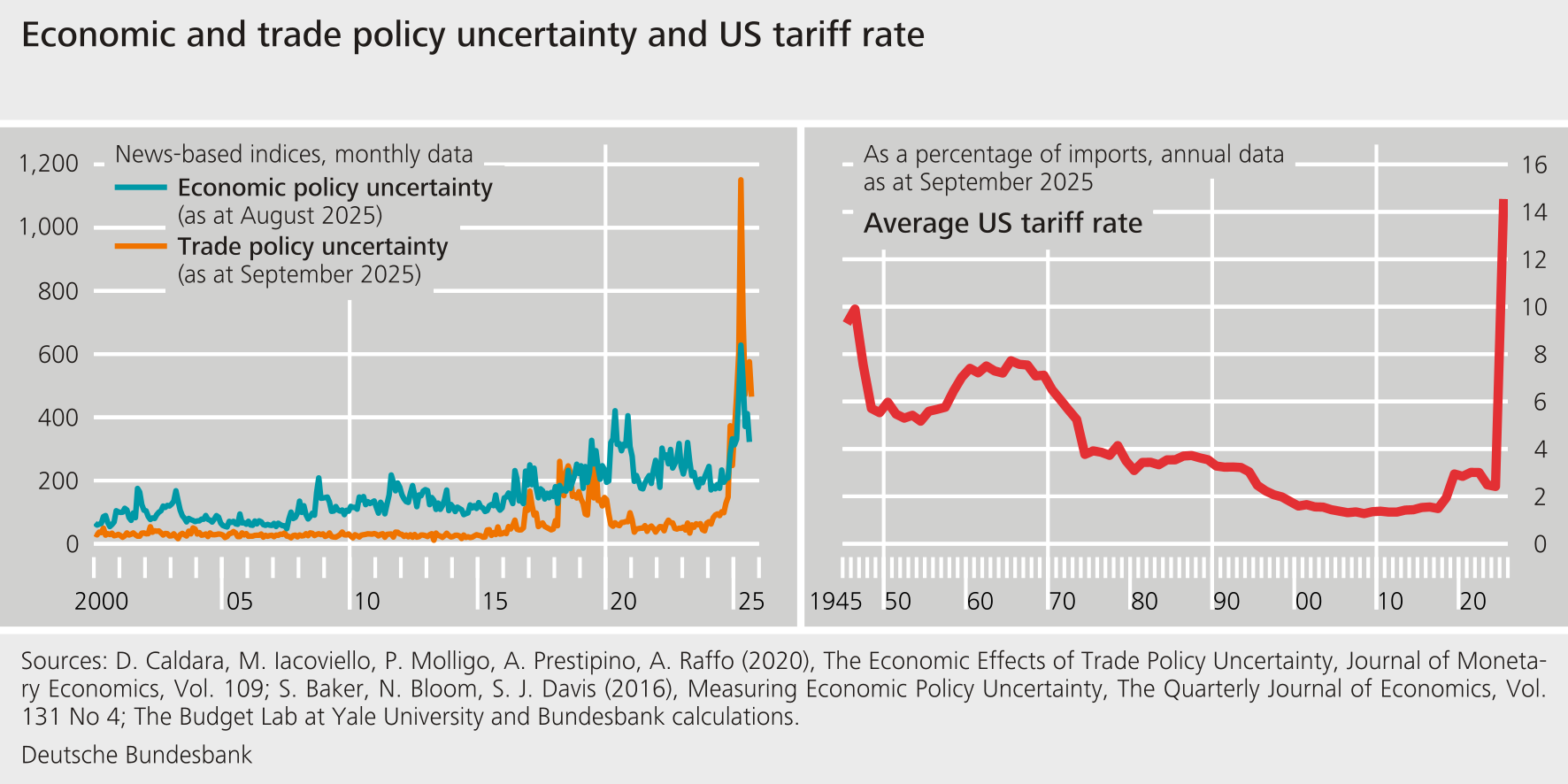

Ladies and gentlemen, the erratic course of US trade policy is weighing on the global economy, not least on Germany’s export-dependent industry. Since the trade agreement between the European Union and the United States was reached at the end of July, imports from the EU have been subject to an average tariff of 14 % (see the right-hand panel of the chart). This means that tariffs have risen by more than 12 percentage points compared with the situation before. Thus far, however, the agreement is only a political memorandum of understanding and is not legally binding, and the legality of the tariffs has not yet been fully clarified. US trade policy therefore remains a significant factor of uncertainty (see the left-hand panel of the chart).

At present, we are experiencing a period of economic weakness. Current forecasts are predicting weak economic growth of around 0.2 % for this year. In addition, we are also facing longer-term structural challenges, such as demographic change, large bureaucratic burdens, sharply risen energy costs, and growing competition from emerging markets. We expect that potential growth will stand at only 0.4 % over the next few years. In order to put the German economy on a sustainable path of growth, decisive action must finally be taken to implement structural reforms. This would also bolster financial stability.

At the same time, the threat of cyberattacks and hybrid attacks is growing. We need to expand our digital infrastructure, but this has increased the potential targets for cyberattacks. It is crucial to further strengthen the cyber resilience of the financial sector. Institutions must therefore invest more in their IT security.

2 Rising government debt: risks to financial stability

Another focal point is the potential consequences of high government debt, both in Europe and around the world. In the past, the Bundesbank has repeatedly highlighted the risks to financial stability that arise from this.

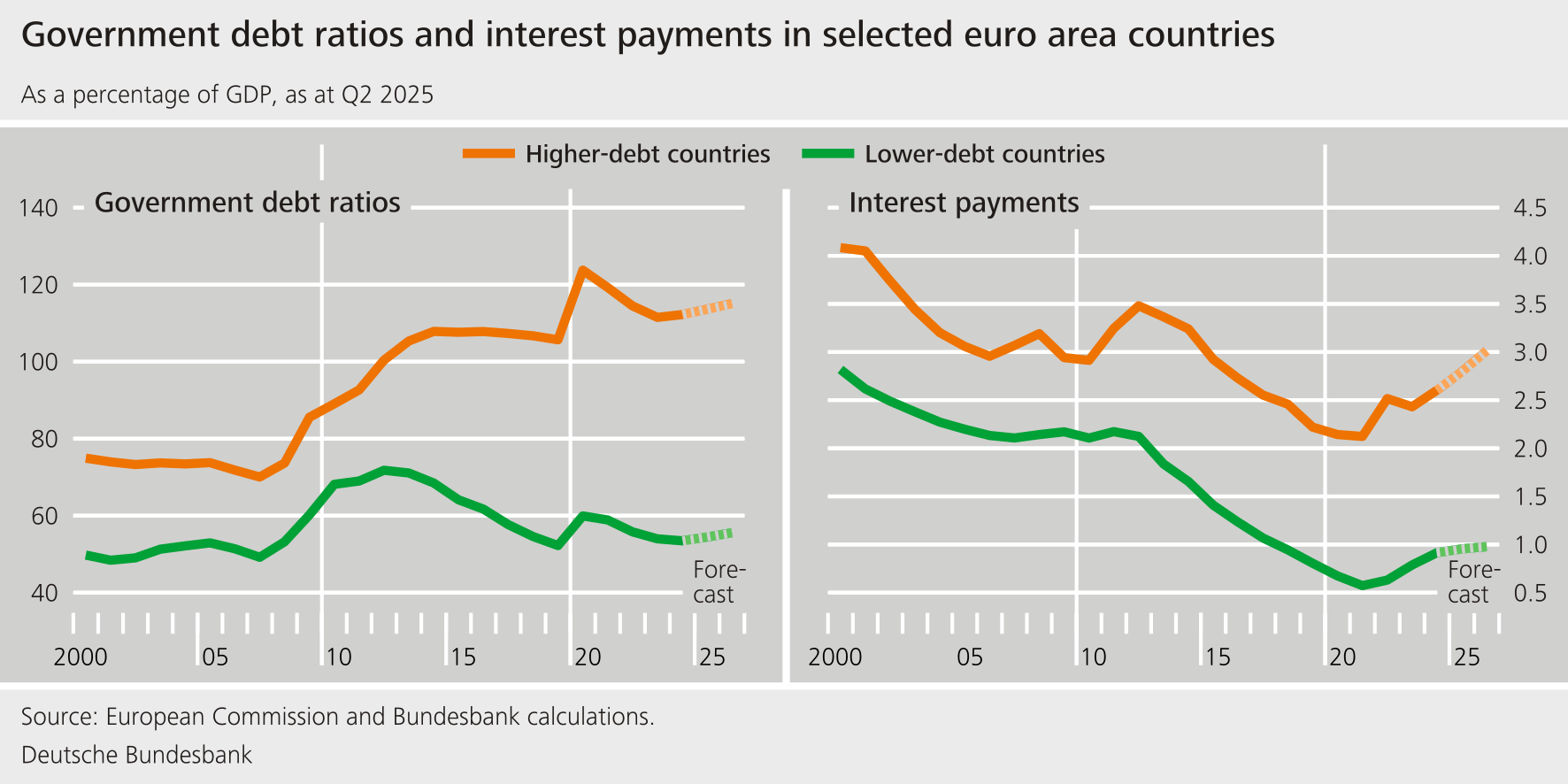

High government spending and low growth have led to a further increase in debt in Europe, especially – but not only – in the more indebted countries (see the chart). In Germany, too, the debt ratio is rising due to the financial burdens caused by the fiscal package, though this is likely to be manageable. However, the recently amended national fiscal rules will guarantee neither long-term sustainability nor compliance with EU fiscal rules, which will possibly necessitate fiscal policy adjustments in the medium term.

In order for debt to remain sustainable, Europe must achieve persistently stable economic growth. Structural reforms must be accompanied by stringent and credible fiscal rules. As an economically important and creditworthy Member State, Germany bears particular responsibility here as a role model and an anchor of stability for the monetary union.

3 Credit and assets: state of the financial cycle

Let us now turn to the current state of the financial cycle and take a look at developments in lending and asset prices.

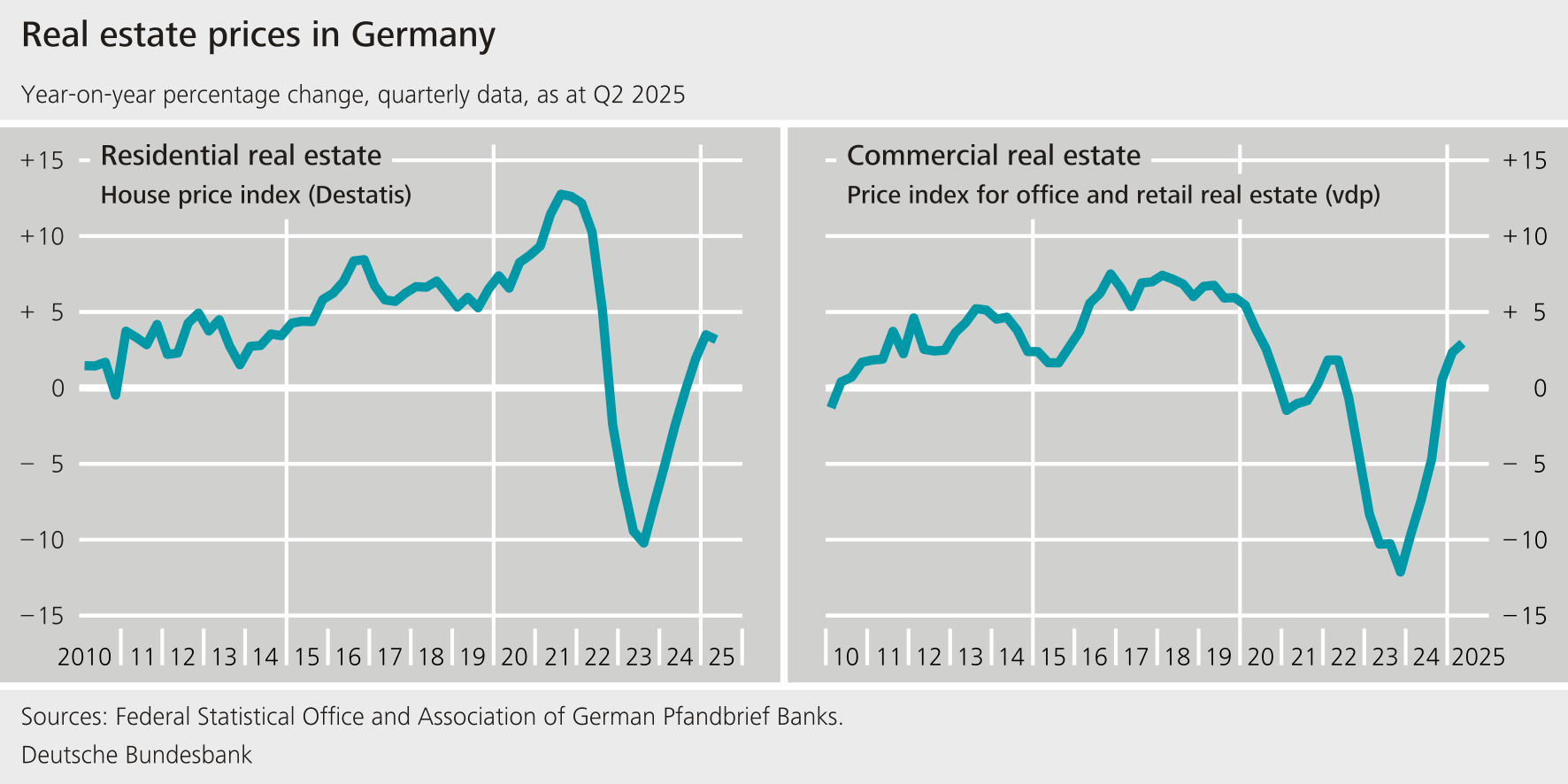

With regard to the housing market in Germany, price developments are now pointing towards recovery (see the left-hand panel of the chart). After the COVID-19 pandemic, prices initially saw significant declines. Since the end of last year, prices have been on the rise again. Overall, past overvaluations have largely diminished. In the German commercial real estate market, by contrast, the situation remains fragile. Although prices seem to have stabilised here recently, too, future developments remain uncertain (see the right-hand panel of the chart). As we know, this sector is particularly sensitive to developments in economic activity and long-term interest rates.

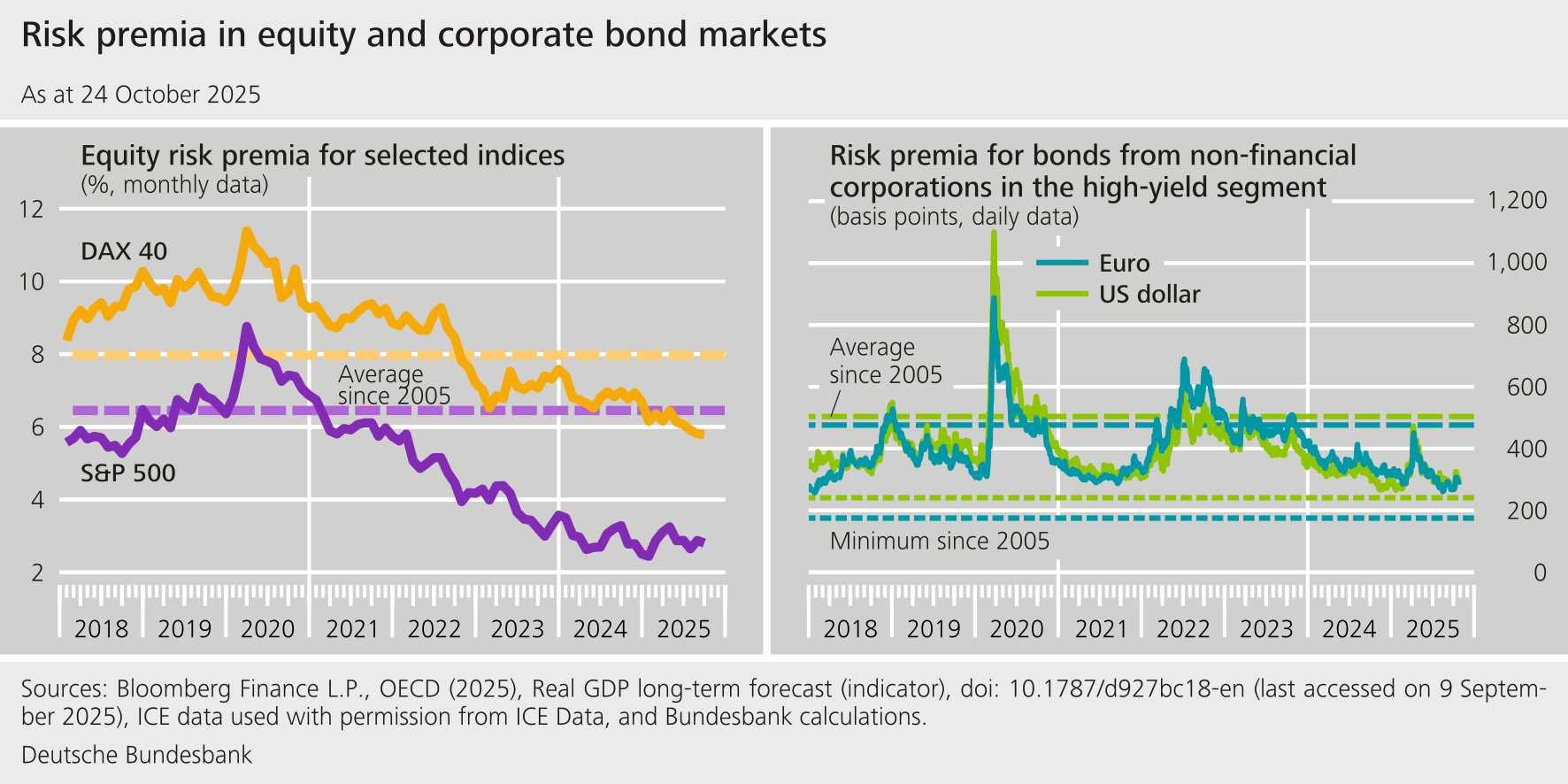

In my view, the high valuations in financial markets are a cause for concern. Risk premia in equity markets are below their long-term averages, especially in the United States (see the left-hand panel of the chart). And, despite the deteriorated environment, risk premia on corporate bonds are even approaching their all-time lows again (see the right-hand panel of the chart). Experience has taught us that markets can change their assessments in an instant. Market price corrections could then trigger considerable losses among financial intermediaries.

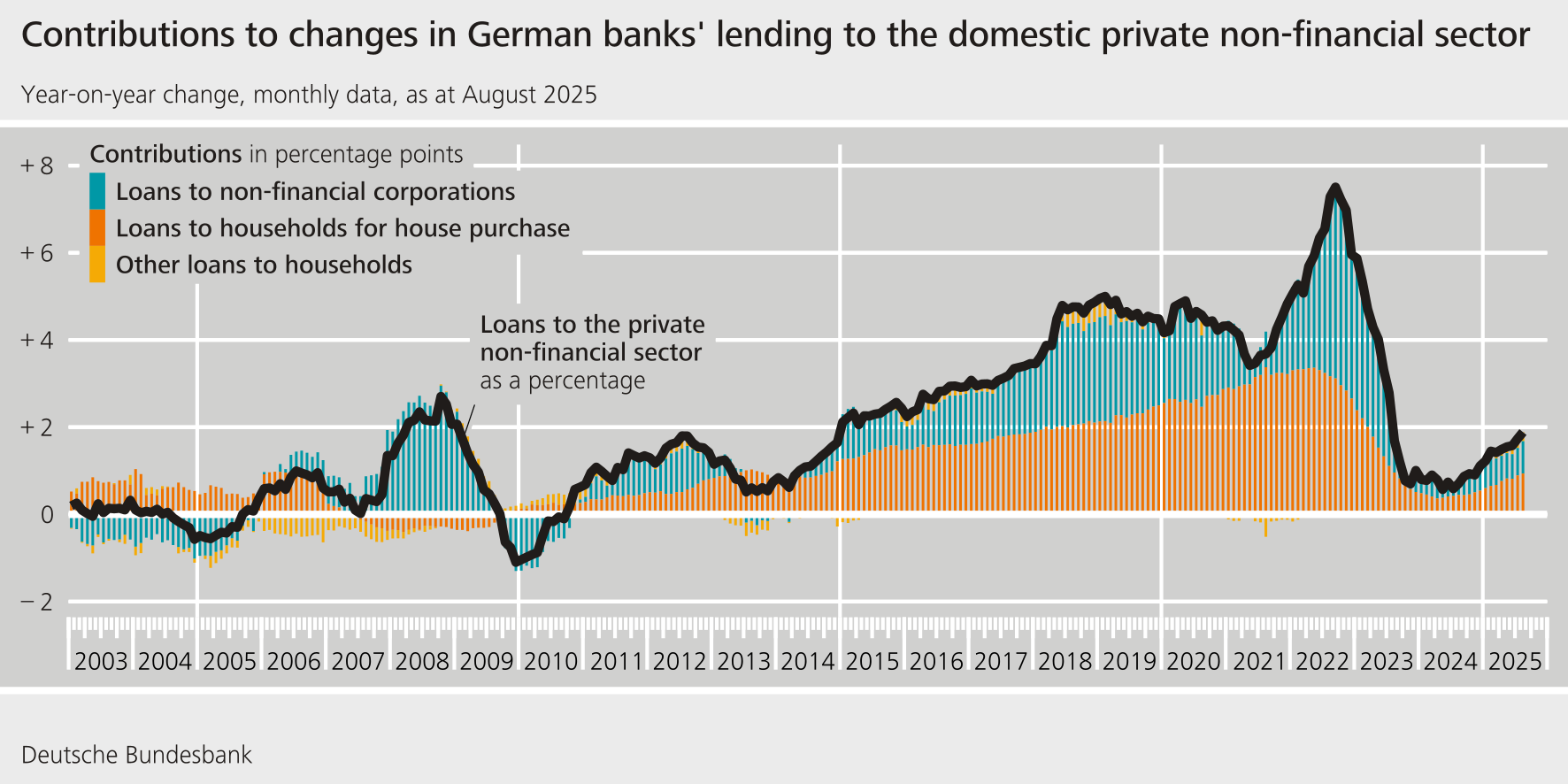

Lending by the German banking sector is now showing signs of slight recovery (see the chart). After the rise in interest rates in 2022, there was a significant decline in lending. Now, lower interest rates and higher incomes are supporting demand for residential real estate loans again. Lending to enterprises has also risen slightly. All in all, the developments in asset prices and lending are indicative of an upswing in the financial cycle, even though future developments are still uncertain.

4 State of the financial system: the situation for banks

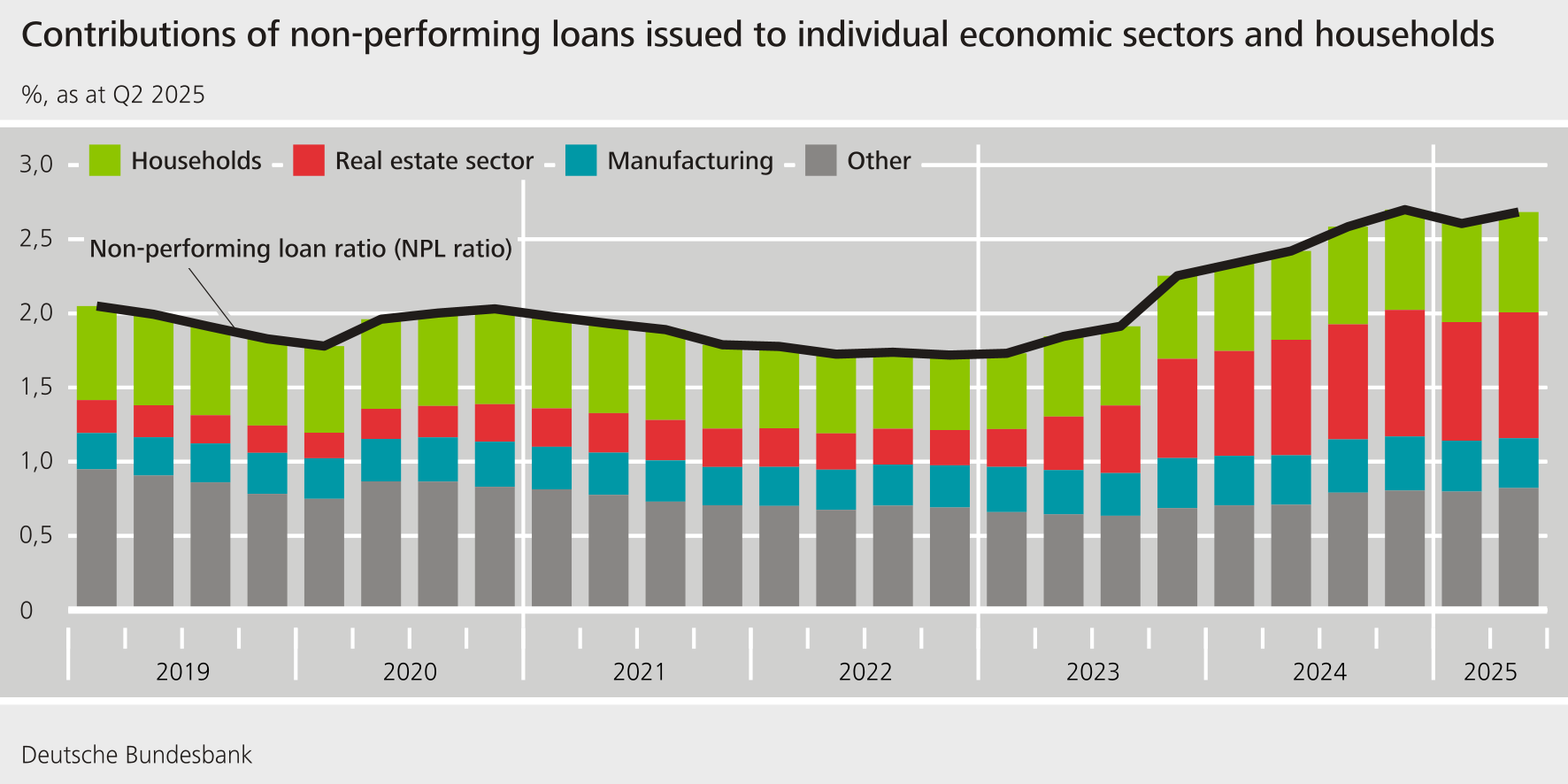

What impact is the changed macro-financial environment having on the German financial system? As we reported last year, banks have seen their stocks of non-performing loans rise steadily since the end of 2022 (see the chart, black line). This development now appears to be becoming entrenched. Whilst it was mainly the commercial real estate sector that was affected at first (see the chart, red bars), the economic downturn is now spreading to other sectors, albeit to a lesser extent. Overall, however, the credit defaults are within manageable territory. Nevertheless, banks are increasingly needing to make value adjustments to their loans. This is weighing on profitability, which is still benefiting from high interest income at present. Looking ahead, the high US tariffs are likely to lead to further value adjustments. Based on our assessment, the immediate risks to the German banking system appear limited, as the banks’ exposure to the affected sectors is limited overall.

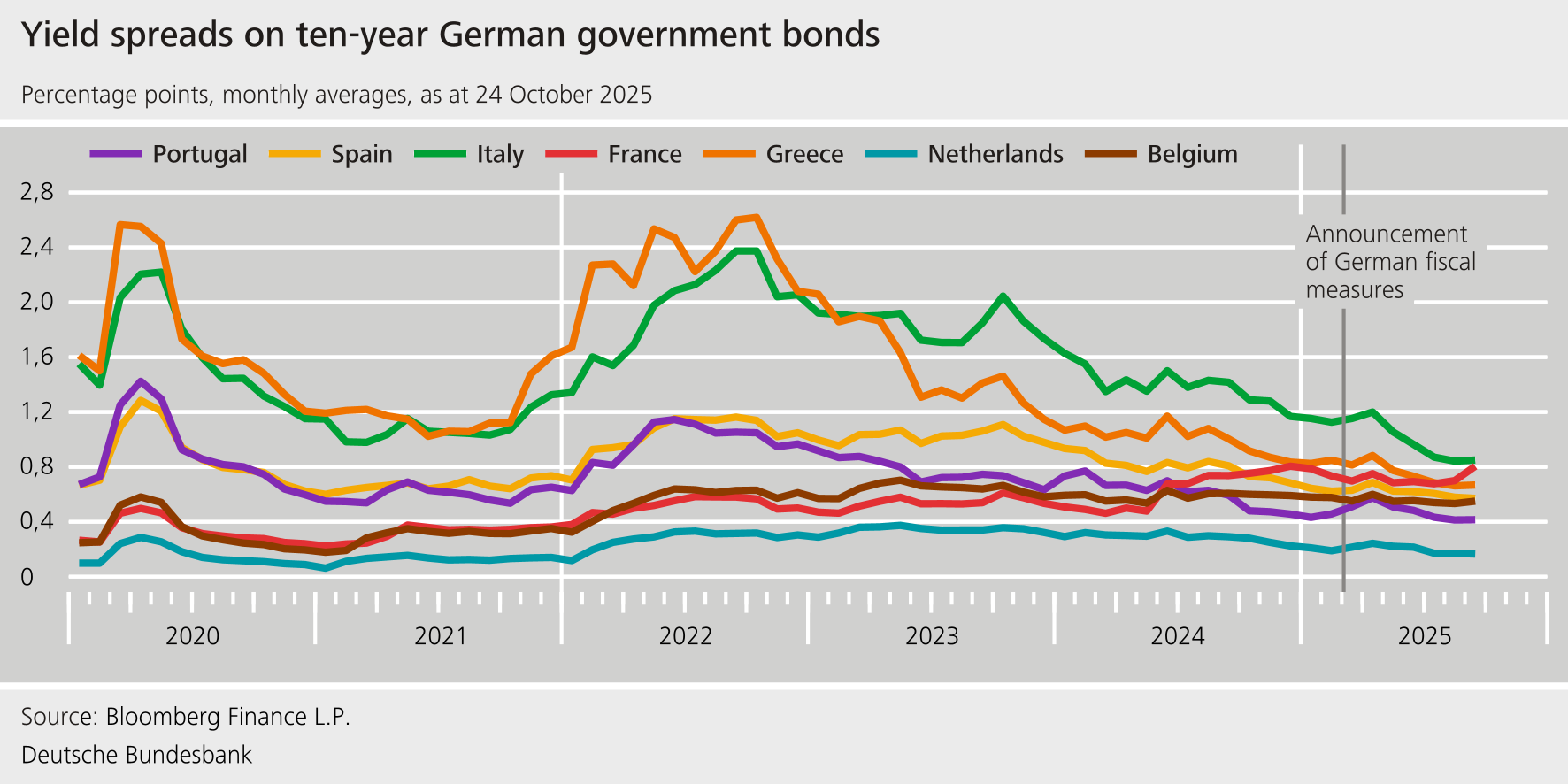

In the Financial Stability Review, we also look at market risks related to the high levels of government debt in Europe that I mentioned earlier. We can see that yield spreads over German government bonds have narrowed considerably since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic (see the chart). Favourable growth expectations are likely to have contributed to this. However, if these fail to materialise and the prices of bonds then suddenly fall, banks could suffer considerable losses.

In a scenario analysis, we examined how large these losses could be for German banks. As our baseline, we used surges in yields as observed during the euro crisis from 2010 to 2012. The investigations revealed that, for the vast majority of banks, the immediate losses would probably be quite manageable. Nevertheless, there would be a significant reduction in excess capital. More severe would be the additional losses that could be caused by contagion effects from other European countries. This is because German banks are interlinked with foreign banks via lending, and these banks, in turn, have large holdings of government bonds from their respective countries.

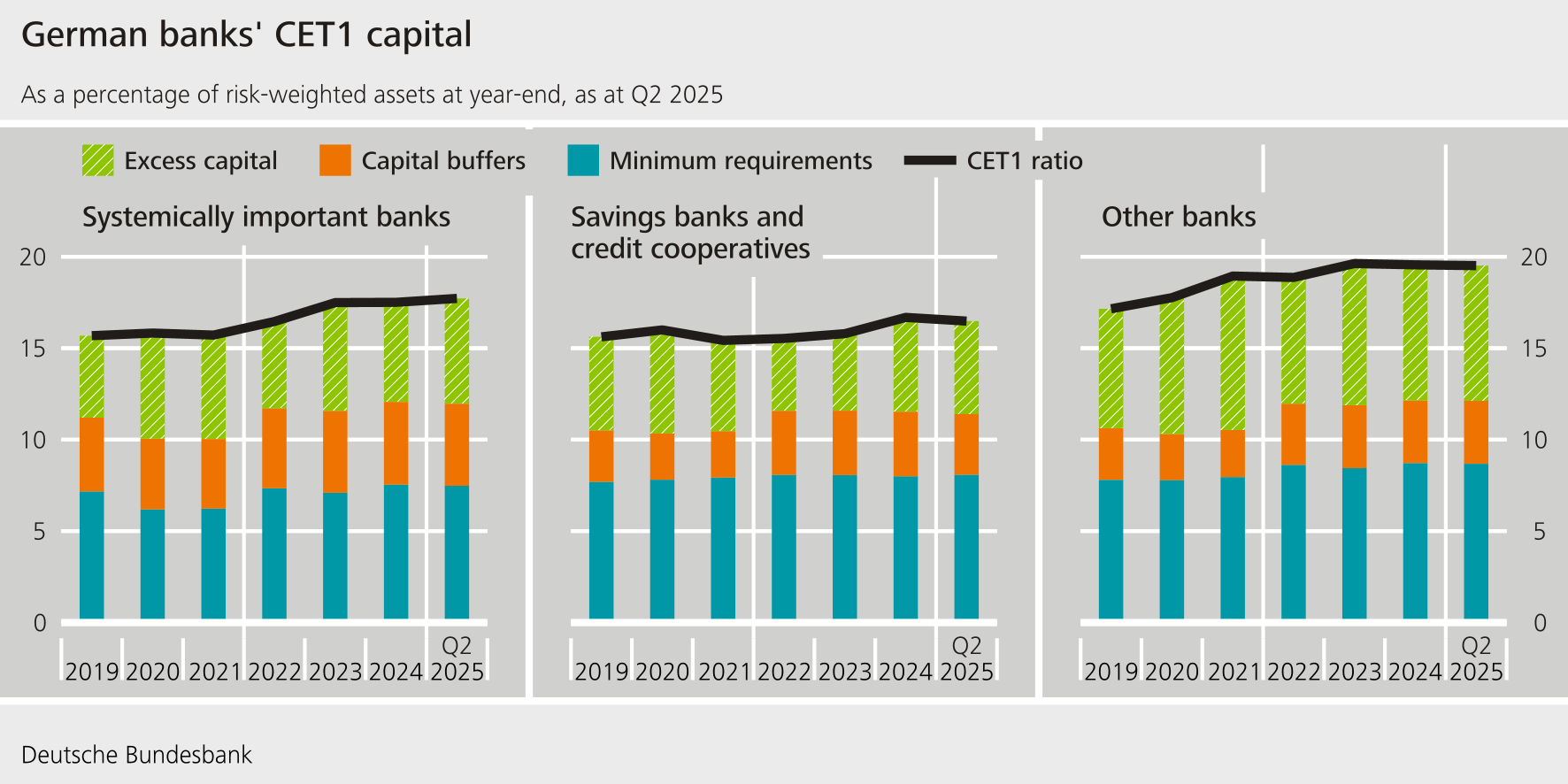

In the past, the Bundesbank has repeatedly stated that banks need to have sufficient capital. This is because banks can then absorb incurred losses without restricting their lending. I am pleased to say that the regulatory capital ratios of German banks are high, not least because of the macroprudential capital buffers (see the chart). However, a role has also been played by the fact that risk weights are low. This affects large, systemically important banks, in particular. So far, we have seen no indication that the deteriorated risk situation has led to an increase in risk weights. To this extent, the regulatory capital ratios could suggest a degree of resilience that is actually lower in some parts of the banking system.

5 NBFIs: growing importance and systemic risks from interconnectedness

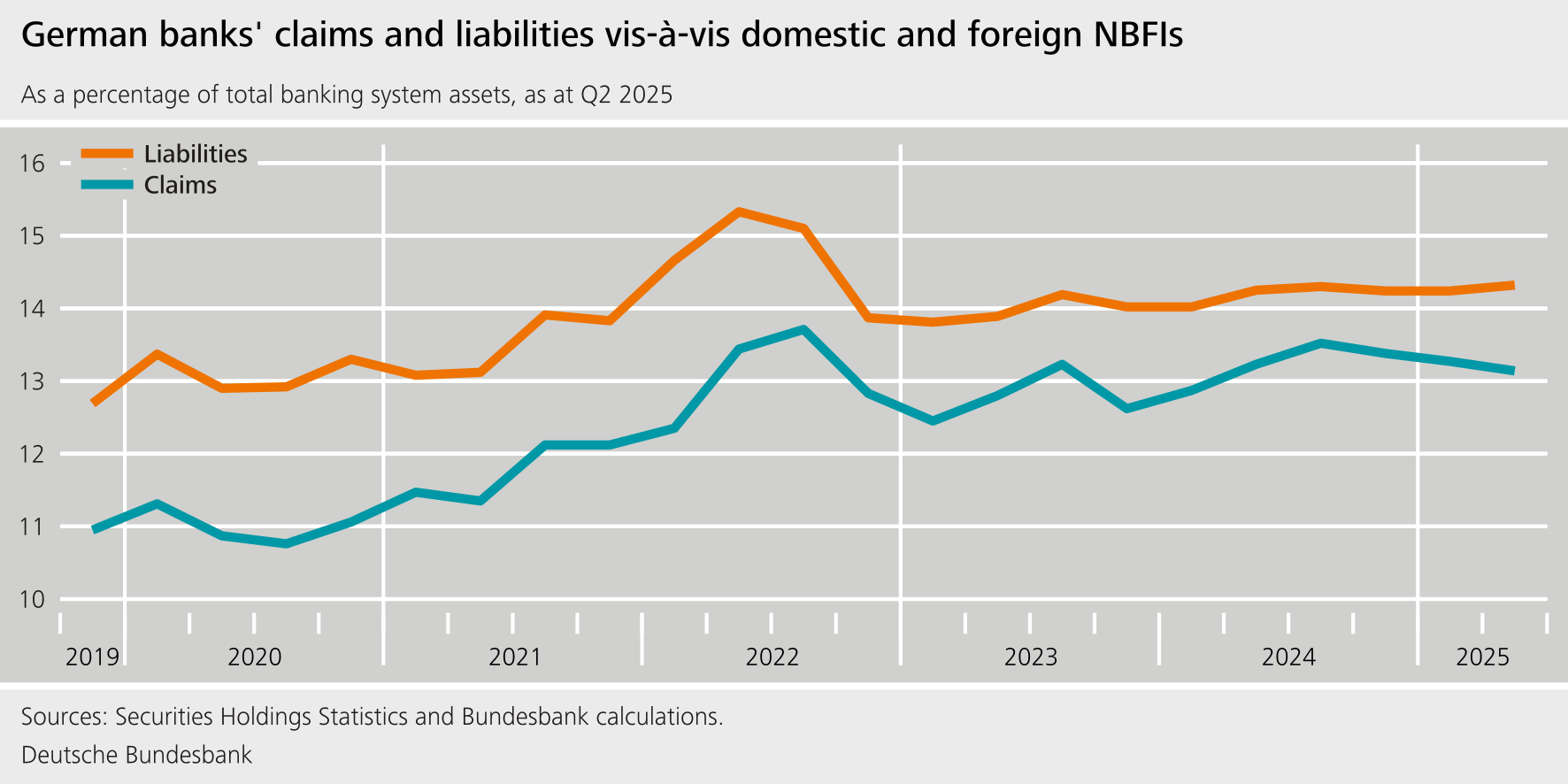

Now I would like to turn to the situation among non-bank financial intermediaries, or NBFIs. The NBFI sector is becoming increasingly significant around the world, including in Germany. Here, the NBFI sector comprises insurance companies and funds, in particular. NBFIs are interconnected with each other, but also, above all, with banks (see the chart). Amongst other things, they are an important source of funding for credit institutions. Large, systemically important German banks, in particular, are strongly interconnected with foreign NBFIs. Shocks originating abroad could be transmitted to the German financial system through this channel. However, German insurance companies and funds, too, are directly connected with foreign NBFIs.

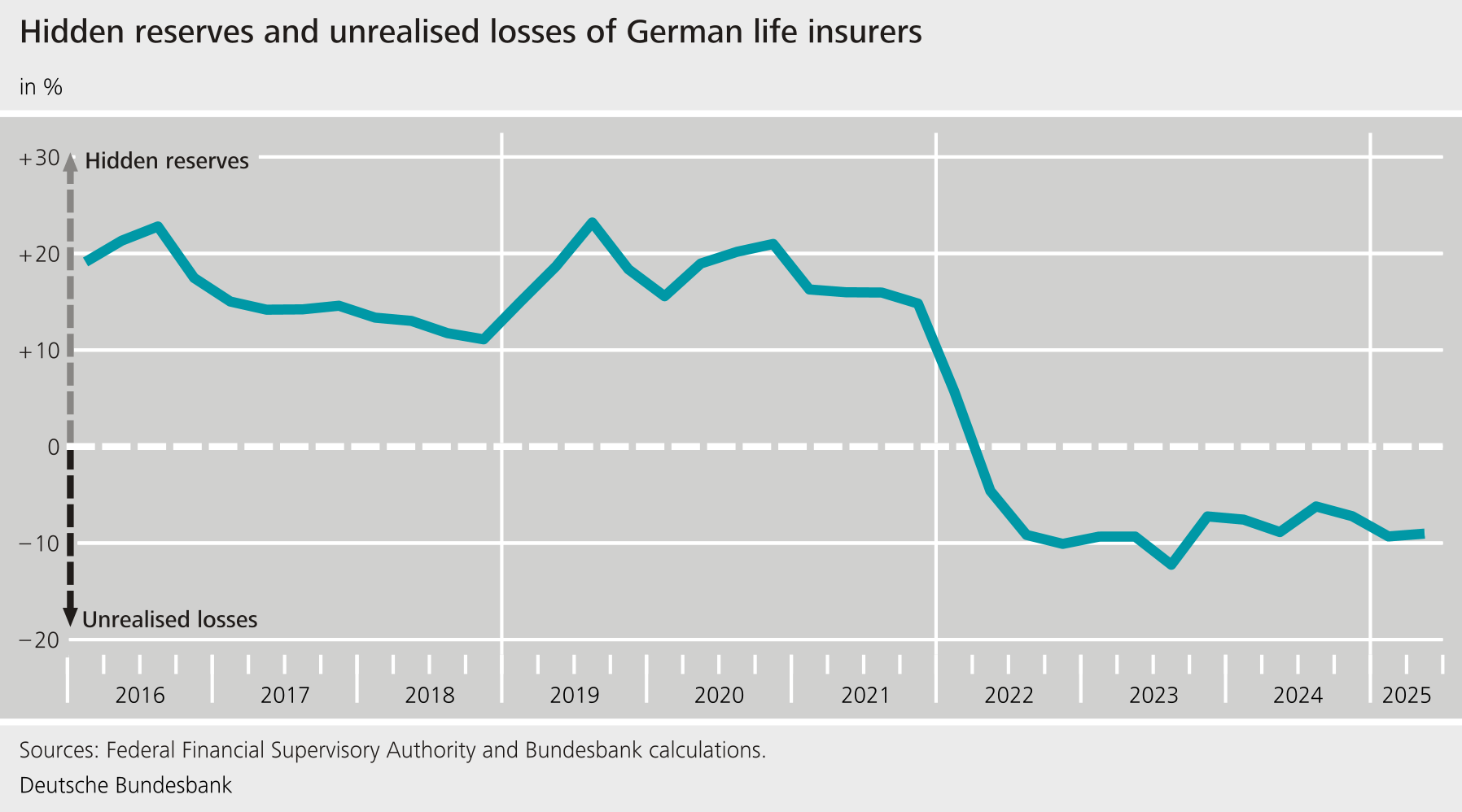

Alongside direct connections, indirect connections also play an important role. For example, German stakeholders often hold the same or similar securities as foreign stakeholders. The global financial crisis taught us that fire sales that one stakeholder might be forced to make may lead to price drops and corresponding losses amongst other stakeholders. In some cases, this can have severe consequences for financial stability. Overall, however, our assessment is that the NBFI sector appears robust. Nevertheless, the insurance sector continues to be faced with material unrealised losses from the period of sharply higher interest rates (see the chart). Insurance companies could therefore aim to avoid sales and restrict their trading activities. From a financial stability perspective, this would be a cause for concern, as insurance companies have been a stabilising factor in financial markets in the past.

The German fund sector appears resilient overall, too. However, the US tariff announcements from April this year have revealed vulnerabilities among German open-end retail securities funds. For instance, these experienced distinct outflows of funds, which had marked consequences for their liquidity positions. The situation eased again as trade policy uncertainty subsided. For retail real estate funds, the notice periods and minimum holding periods introduced in 2013 have proved to be effective.

6 Resilience: final assessment and implications for macroprudential policy

What conclusions for macroprudential policy can we draw from our analysis of financial stability?

We consider the package of macroprudential measures to be appropriate. As you may know, at the beginning of 2022, the German regulator announced a package of macroprudential measures, including a countercyclical capital buffer and a sectoral systemic risk buffer, in order to address emerging systemic risks in the financial system. We believe that the countercyclical capital buffer, at its current level, remains necessary given the ongoing risks. The sectoral systemic risk buffer was lowered from 2 % to 1 % in April, as vulnerabilities in residential real estate financing had been partially, but not fully, resolved.

Nevertheless, it appears that now is the time to simplify current banking regulation. At present, banks have to fulfil capital requirements for a variety of purposes. We support simplifying a range of requirements. And if we reduce double counting, the macroprudential buffers could be utilised more effectively. We therefore advocate that, amongst other measures, the countercyclical capital buffer and the systemic risk buffer should be combined into a single capital buffer. We also want regulatory requirements to be simplified for small, non-complex institutions. We could dispense with complex, risk-weighted capital requirements if we instead applied more stringent, non-risk-weighted capital requirements.

In the area of NBFIs, we need to improve the availability of information regarding cross-border interlinkages. This would considerably deepen our perception of risk and could close potential regulatory gaps. When I talk about improving the availability of information, I primarily mean making it easier to access pre-existing data. Central banks and supervisory authorities in Europe should share existing data to a greater extent. We are committed to ensuring that the legal framework conditions are adapted where necessary.

I would like to follow up on the quote I mentioned at the beginning of my presentation and conclude this overview of financial stability with a quote from Pericles of Athens:

“The key is not to predict the future, but to prepare for it.”

In other words: we cannot know with certainty how the global economy and global financial architecture will evolve. But we have a duty to prepare for unforeseeable events with appropriate regulation and risk-oriented supervision.

7 Concluding remarks

This brings me to the end of my comments on the current risk situation for the German financial system.

This year marks the twentieth edition of our Financial Stability Review. We are celebrating this anniversary by hosting a small conference with interesting guests and engaging discussions. For those of you who cannot be here with us in person, a recording of the conference will be available on the Bundesbank’s website next week. I hope you will take a look.

I now look forward to taking your questions.