Central bank independence and the mandate – evolving views Remarks prepared for the international high-level symposium in honour of Stefan Ingves

Check against delivery.

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a privilege and honour for me to speak here today on the occasion of the farewell of Stefan Ingves and to participate in this distinguished panel. Governor Ingves was one of my first points of contact when I joined the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) more than a decade ago. He has been a leading figure in the ESRB from the beginning and thus, one can argue, he is one of the founding fathers of macroprudential policy coordination in Europe. Over the years, I have learned a lot from him: the relevance of financial stability for the conduct of monetary policy, the need to act in a timely manner as necessary, and the importance of clear communication.

All this is more important than ever at the current juncture, and I would like to make the following points today:

- During the past decade, central banks have enjoyed a "capital of inattention"[2] when it comes to their core mandates. With inflation being low and a stable financial system, the public could pay limited attention to price and financial stability – and entrust technocrats in central banks with the details of the actual conduct of these policies.

- Current macroeconomic developments challenge price and financial stability. Inflation is one of the main concerns of the public. Concern about higher prices – notably energy prices – is likely to remain elevated even if and when inflation rates recede. Moreover, vulnerabilities in the financial system have been building up over the past decade. All this moves central banks into the spotlight of public policy discussions.

- Explaining the role of central bank independence and – more importantly – to act accordingly will become both, more difficult and more important. In an environment with high levels of debt and high inflation, tensions between fiscal and monetary policy can surface. Moreover, central banks have assumed a broader range of responsibilities over the past decade. Central banks have mandates to both ensure price stability and contribute to financial stability. While, in the longer term, all policy areas benefit from financial stability and stable prices, conflicts of interest can surface.

- Central bank independence is protected by institutional safeguards. In Europe, primary law assigns a strong role to central bank independence, central bank governors have terms of office which are decoupled from the regular electoral cycles, and central banks enjoy a high degree of operational independence. In addition, complementary institutional frameworks and clear rules are needed that delineate the role of monetary, fiscal, and macroprudential policies. Absent such frameworks, monetary policy can come under fiscal or financial dominance.

- Transparency, accountability, and communication are equally important to sustain public support of independence. This can be a balancing act: On the one hand, transparency requires a structured policy cycle. Evaluation frameworks are needed to link policy objectives to policy instruments and to analyse the intended and unintended consequences of policy choices. Such evaluation frameworks are of a rather technical nature and tuned to an expert audience. On the other hand, the general public needs to be convinced that the central bank acts in the public’s best interest and that non-elected technocrats protect the public good “stability”. Translation from the language spoken by technocrats to the language spoken by the general public is an art rather than a science. This translation and a continuous dialogue with the public are crucially needed though – in particular in times of structural change and a high degree of uncertainty about the future.

1. (New) challenges for central bank independence

[3]With inflation rates running up to 10% in the euro area, the core mandate of central banks – price stability – is a key policy issue today.[4] According to a Eurobarometer poll conducted in the fall of 2022, 42% of respondents in Europe mention rising prices and (high) costs of living as the most important issues facing the EU.[5] This number has increased by 8 percentage points since the summer. Other main risks such as energy supply (29%) and the international situation (20%) rank second and third.

The macroeconomic situation has indeed changed quite radically, which has implications for the perception of central banks. Over much of the past decades, as inflation was low, central bank independence has hardly been at the centre of public policy debates. There has been "rational inattention" with regard to inflation and the core mandates of central banks.

Central bank independence mitigates direct political intervention into their policy objectives. Independence refers to the “how to” achieve its policy objectives: A central bank is free to make decisions about the tools it employs, subject to legal constraints that are set out in its charter.[6] The central bank’s objectives – the “what to” achieve – are determined by the government, while the central bank may enjoy discretion with respect to the clarification of its objectives.[7]

Central bank independence reduces the time inconsistency problem of monetary policy as well as the risk of fiscal and financial dominance. A policy is time inconsistent if an action, optimally planned today for tomorrow, is not optimal anymore when tomorrow arrives.[8] If a central bank has announced a low inflation rate, it may be tempted to depart from this announcement. Surprise inflation could generate a positive output effect – but at the risk of losing credibility. Additionally, if fiscal policy is weak, there can be the temptation to keep interest rates low for longer in order to generate seignorage revenues.

Similarly, policy decisions related to financial stability require independence. As vulnerabilities in the financial system build up during good times, macroprudential authorities should act early on in a preventive manner. Sufficient capital buffers need to be generated that can absorb losses in times of crisis. However, authorities may act too late or too little if they fear negative - short-term - implications for credit growth or bank profitability. In the medium- to longer-term, insufficient buffers in the financial system can threaten fiscal stability by forcing the public sector to intervene and absorb losses in times of crisis. This inaction bias can be remedied by assigning the task to safeguard financial stability to an independent authority.

What are current challenges? And could central bank independence be at risk? I see three main reasons why central bank independence may move into the focus of public policy discussions:[9]

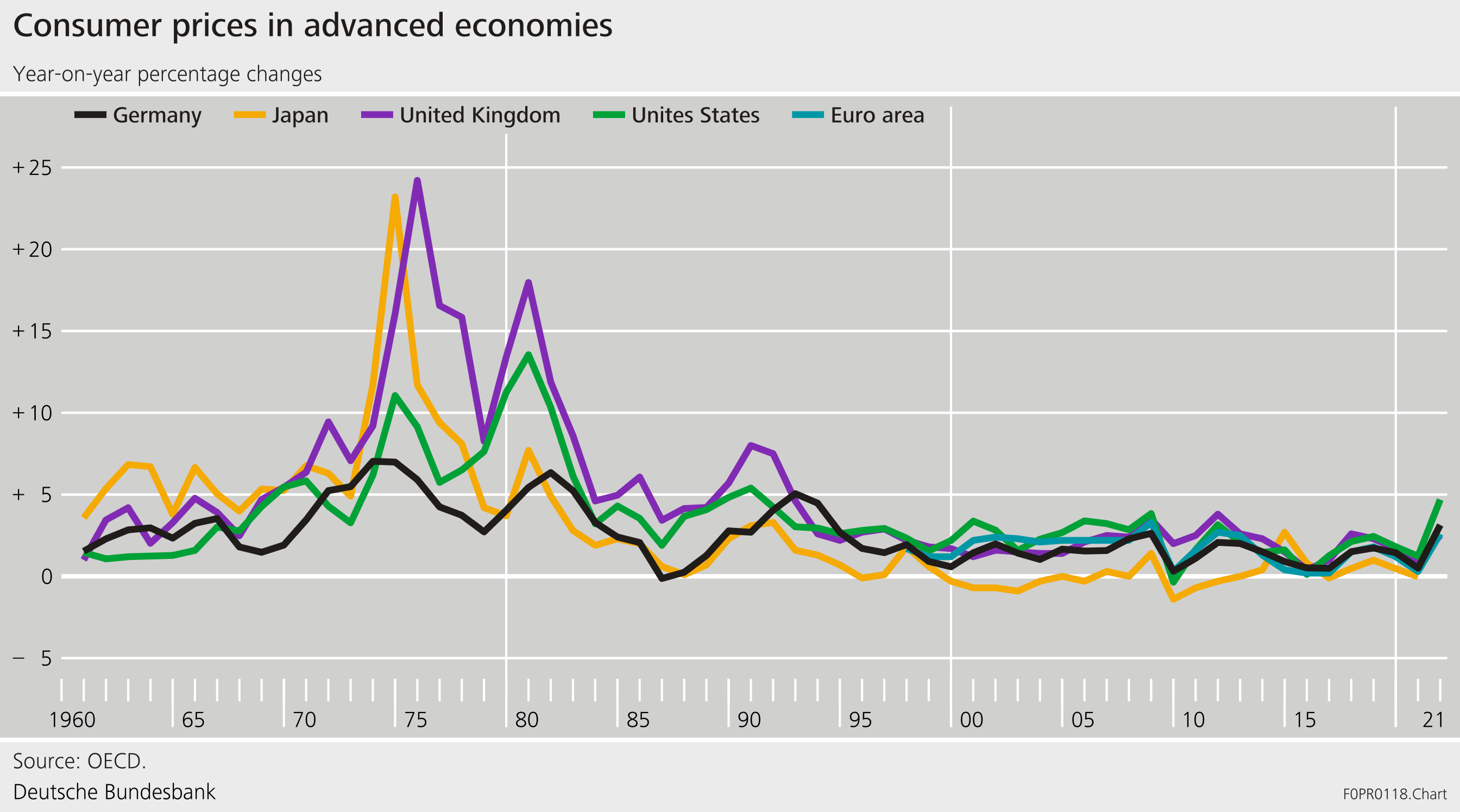

First, inflation is expected to remain comparatively high over the next couple of years. The past decade has witnessed relatively low and stable inflation across advanced economies (Graph 1). Yet, more recently, demand and supply shocks have pushed inflation well above central banks’ targets (Reis 2022b). According to the most recent projections by the ECB, inflation will return to target only by the year 2025.[10] And even if actual inflation rates decline, perceived inflation – notably in terms of higher energy prices – will remain at an elevated level. Some structural features of the global economy, which have kept inflation low over the past decade, may reverse and contribute to higher inflationary pressure in the future (Goodhart and Pradhan 2020).

Second, vulnerabilities in the financial system and risks to financial stability have increased. According to the ECB's financial stability report and a warning issued by the ESRB, financial stability conditions in Europe have deteriorated.[11] Our assessment of the situation in Germany is quite similar.[12] After a long period of low interest rates, low corporate insolvencies and accordingly low credit risk, the Bundesbank has particularly warned that future macroeconomic risks may be underestimated. Should risks to financial stability materialize, the causes and the role of central banks in maintaining financial stability would move into the limelight.

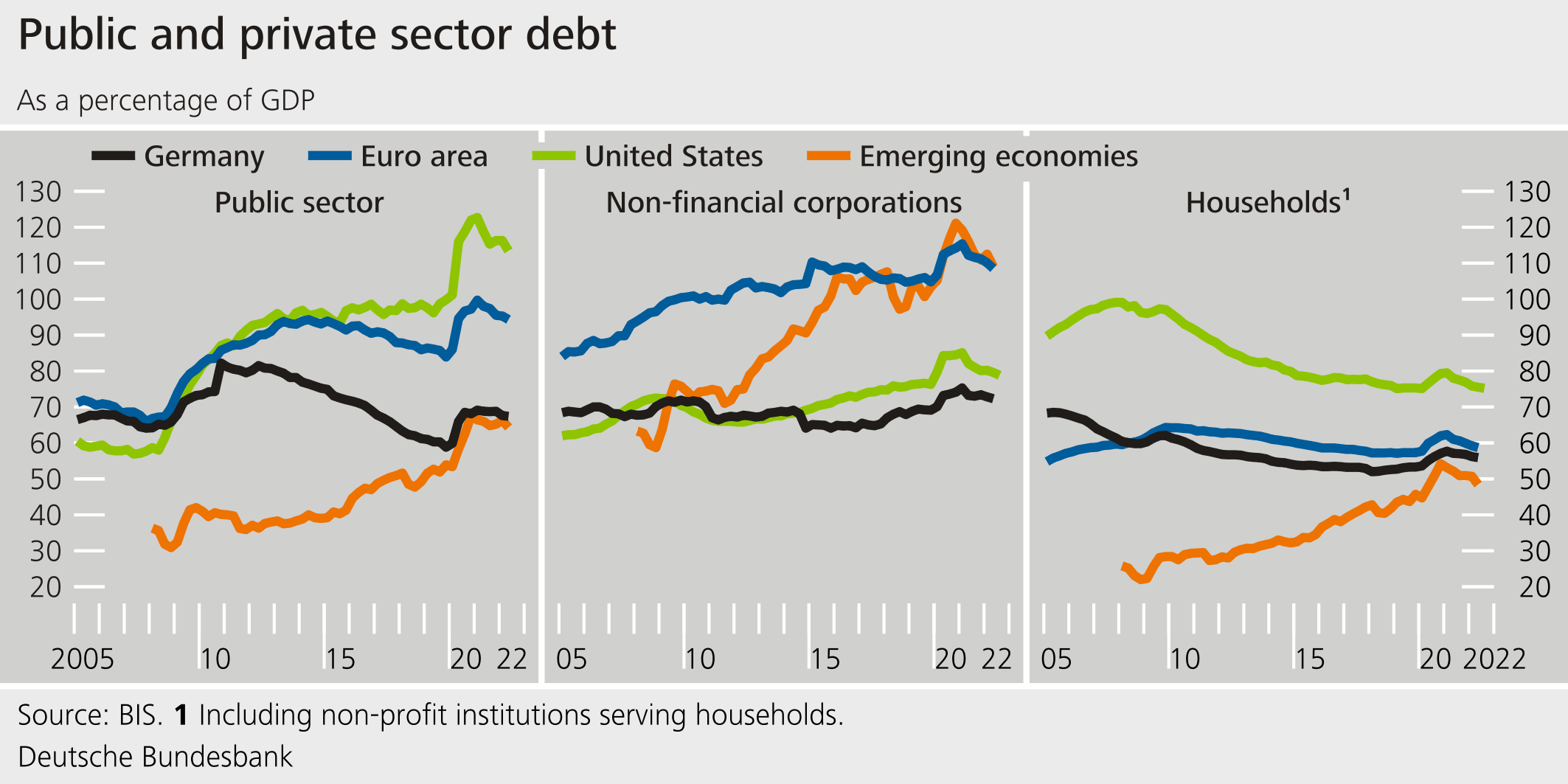

Third, high levels of debt can lead to conflicts between price and financial stability. Debt has increased, in many countries and across sectors (Graph 2). Historically, high leverage has created stress in the financial system and put pressure on central banks to monetize debt (Reinhard and Rogoff 2009). At the current juncture, higher interest rates are needed to fight inflation and to anchor inflationary expectations. But higher market interest rates may also threaten debt sustainability and financial stability, in particular if such higher rates materialize abruptly. Absent sufficient buffers in the financial system to absorb losses, central banks might fight inflation less vigorously than needed if they fear adverse consequences for financial stability (Brunnermeier 2016, Reis 2022a). Monetary policy may come under fiscal or financial dominance.

Over a longer time horizon, conflicts of interest between monetary policy and financial stability are less acute. If central banks act sufficiently early to address risks to inflation, this also limits risks to financial stability. If, however, central banks keep interest rates too low for too long, risks to financial stability build up over time. Market participants would continue to search for yield, and banks’ risk models would continue to underestimate risks. Financial institutions may – implicitly – even engage in risk taking collectively if they anticipate such monetary rescues (Farhi and Tirole 2009, 2012).

The global financial crisis has shown an unclear division of labour between monetary and fiscal authorities can potentially put the credibility and independence of central banks at risk. As buffers in the private financial sector against adverse shocks turned out to be insufficient when the crisis struck in 2007/2008, eyes turned to central banks as providers of liquidity in times of stress. Yet, central banks lacked clear-cut guidelines and operating principles for their lender-of-last-resort and market-maker-of-last-resort activities (Tucker 2018). Also, it quickly became evident that authorities were not just dealing with liquidity issues but with solvency problems of financial institutions. Lacking adequate resolution frameworks and sufficient loss absorbing capacity in the financial sector, fiscal funds were used to rescue financial institutions.

When the crisis struck, drawing a clear line between monetary and fiscal policy was often difficult given the lack of clear institutional frameworks. Eventually, central banks engaged in quasi-fiscal operations by lending to distressed, illiquid financial institutions threatened by insolvency (Buiter 2014, Tucker 2018). Risks on central banks’ balance sheets increased. Hence, the ability of central banks to pursue price stability can be under threat if fiscal authorities are unwilling or unable to bear risks and if the central bank steps in. It has thus been argued that the central bank in its function as a lender- and market-maker-of-last-resort needs a fiscal backstop (Buiter 2014, Sims, 1999, 2001, Tucker 2018).

Since the global financial crisis, the regulatory framework has been significantly changed. Capital requirements have been enhanced in order to increase resilience of banks, resolution frameworks have been institutionalized, loss-absorption capacity has been increased, and supervision has been strengthened.[13] All this is very welcome – but it also requires a constant process of monitoring the progress that has been made, the extent to which risks have moved to other parts of the financial system, and the willingness to act and apply the new tools as needed.

2. Central bank independence requires strong institutional frameworks

At the current juncture, risks to price and financial stability are heightened, and conflicts of interest can arise unless adequate institutional frameworks are in place. The key institutional anchor of central banks, their independence, is not at the centre of current policy discussions. This suggests that the public has a high level of confidence in the ability of central banks to perform up to their tasks.

In Germany, this trust has been supported over decades by a broad societal consensus about the institutional role of the Bundesbank. This consensus has been codified legally. The Bundesbank Act[14], Section 3, stipulates that “It shall participate in the performance of the ESCB's tasks with the primary objective of maintaining price stability, shall hold and manage the foreign reserves of the Federal Republic of Germany, shall arrange for the execution of domestic and cross-border payments and shall contribute to the stability of payment and clearing systems.

”

In performing these tasks, the Bundesbank acts independently (Section 12): “In exercising the powers conferred on it by this Act, the Deutsche Bundesbank shall be independent of and not subject to instructions from the Federal Government. As far as is possible without prejudice to its tasks as part of the European System of Central Banks, it shall support the general economic policy of the Federal Government.”

These principles of the Bundesbank’s independence have hardly been questioned ever since the passage of the original legislation in 1957. Prior to independence being laid down in European Union primary law, changing the Bundesbank Act would have been feasible with only a simple majority in the German parliament. Yet, the Bundesbank’s independence has never been seriously contested by political actors. Substantial changes to the Bundesbank Act that have been made over time were related to major events such as German reunification[15] and the introduction of the Euro[16]. None of them touched upon Bundesbank’s independence. It is interesting to note though that the societal consensus for independence has formed over time, reflecting experience with spouts of hyperinflation and observed actions of the central bank after World War II.[17]

This broad societal consensus in favour of central bank independence has also carried over to the European level. [18] Trust of the population has been justified by the low-inflation policies since the foundation of the ECB: Inflation has been lower than during the preceding decades, in particular during the turbulent 1970s (Graph 1 and Reis 2022b). A number of arrangements protect the ECB’s independence: separate budgets, sufficiently long terms of office, no reappointment of members of the Executive Board, prohibition of monetary financing, functional independence, and the ECB’s right to adopt binding regulations necessary for carrying out its tasks. This protection of the ECB’s independence is rather strong as changing the treaty would require unanimity (Goodhart and Pradhan 2020).

In combining a clear mandate with operational independence, society has tied its preferences to the central bank’s objectives. This provides democratic legitimization for central banks to impose costs on society in the pursuit of its mandate without considering fiscal consequences (Tucker 2018).

After the global financial crisis, the powers and activities of central banks have broadened, including explicit roles in contributing to financial stability. This raises a number of questions: How to balance the new roles, mandates and potential conflicts of interest? How do financial stability, macro-and microprudential objectives and price stability interact? How to avoid the risk of political interference if central banks contribute to macroprudential policies that have distributional consequences?[19]

Answers to these questions need to acknowledge differences between monetary policy and financial stability policies:

First, the time horizon differs. The objective of price stability is defined over the medium-term. Financial stability policies aim at mitigating the build-up of vulnerabilities over the financial cycle, which is longer than the typical business cycle.[20]

Second, the policy objective differs. In its recent strategy review, the ECB’s governing council has defined price stability as an inflation rate of 2%.[21] Defining and quantifying financial stability in a similar way is hardly feasible. Financial stability is about the functioning of the financial system, even in times of stress, without adverse impacts for the real economy (Hellwig 1998) or threatening sustainable economic growth (Allen 2022: 7).

Third, policy instruments differ. Policy rates are the key monetary policy tool, and this tool is firmly in the hands of central banks. There are, in contrast, a number of regulatory policies or fiscal policy instruments that – directly or indirectly – impact the stability of the financial system. Accordingly, financial stability is typically a responsibility shared by supervisory, fiscal authorities, and central banks.[22]

“Independence” in the context of micro- and macroprudential supervision thus differs from independence in terms of monetary policy decision-making. Micro- and macroprudential supervision is coordinated with other authorities. There is no full independence from the political process and, indeed, there should not be, as macroprudential policy decisions can have distributional consequences.

3 Independence requires good communication of central banks

In addition to strong institutions, credibly maintaining central bank independence requires a high degree of accountability and transparency, and clear communication. This communication needs to include the limitations of what can be achieved, as has been stressed by Cukierman et al. (1992: 353): “Institutions cannot absolutely prevent an undesirable outcome, nor ensure a desirable one, but the way that they allocate decision-making authority within the public sector makes some policy outcomes more likely and others less likely.” Twenty years later, Reis (2022b: 5) puts it like this: “…, central bankers followed clear principles – like the Taylor rule of gradualism – that made their actions rule-like in allowing the private sector to understand where policy was heading and why.”

Generally, one key innovation in central bank policy-making over the past decades has been the increase in accountability and transparency. Alan Blinder (2004) calls the increase in accountability and transparency the “Quiet Revolution”, noting that “whereas central bankers once believed in secrecy and even mystery, greater openness is now considered a virtue

.”

Communication has two types of addressees and objectives however. Technical and market experts are the first group targeted by central bank communication. Communicating with this group uses a specialized language, and it can refer to structured policy frameworks. The broader public as the second group does not think in terms of such policy frameworks. Reaching this audience requires a good narrative, translating formal language into more intuitive language in order to ensure broad societal support for an independent central bank.

Communication at an expert-level can follow a structured policy cycle with four interlinked steps.[23] Starting from a broad policy objective, intermediate objectives need to be specified, and appropriate indicators need to be chosen. The decision on whether and how to activate policy measures should be based on a structured process of ex-ante policy evaluation. An ex-ante evaluation provides information about the relative performance of different instruments in contributing to the policy objective. Trade-offs between policy objectives can be taken into account when calibrating instruments. In a fourth step, the effects of the instruments need to be assessed in an ex-post evaluation. This provides information about the effectiveness of the measure(s) taken, about intended or unintended side effects, and it also serves as an input into a possible recalibration of policy instruments.

Following such a policy cycle requires a good infrastructure. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) developed a framework to evaluate regulatory reforms that were implemented following the global financial crisis (FSB 2017). This framework emphasizes the importance of distinguishing the social costs and benefits of the reforms, and weighing the relevance of these requires a societal discussion. Ideally, evaluations need to be carried out by independent experts, and they require a good underlying data infrastructure.

But quantitative policy modelling reaches its limits in times of structural change. The formal models that are used to analyze the macroeconomy and to evaluate policies have features that fail to capture turning points and to address radical uncertainties.[24] Dynamics on financial markets and business cycle fluctuations are shaped by public narratives which do not easily lend themselves to quantitative macroeconomic modelling.[25] These shortcomings are particularly relevant at the current juncture as policy priorities are re-defined and as resilience has become more important.[26] Hence, central banks need to reach out beyond their traditional audiences and expert communities to gather and synthesize information that is relevant for decision-making.[27]

Communication with the broader public, which needs to provide sustained support for central bank independence, requires additional elements. The recent ECB strategy review has thus established a much broader range of tools:[28] visualized approaches, simplified language in the communication of monetary policy decisions, listening events, and a permanent citizen dialogues. In order to explain why financial stability is important, the Bundesbank has developed a video explaining why financial stability is not “boring”.[29]

4. Summing Up

Central bank independence is indispensable for stability-oriented monetary and financial stability policies. At the current juncture, independence may come under threat as risks to price and financial stability have increased. Legal frameworks that protect central bank independence are thus all the more important. Fiscal rules and macroprudential policy frameworks are important complements that mitigate the risk of fiscal and financial dominance.

But legal frameworks are not sufficient. Independence also requires a high degree of accountability and transparency. It requires structured policy evaluations based on central banks’ mandates, and good public communication. Independence allows central banks to act on behalf of the general public – but it does not isolate central banks from the public discourse.

Good communication of central banks can be a balancing act. On the one hand, policy evaluation of a rather technical nature is needed to ensure accountability and transparency. On the other hand, good and coherent narratives are essential to explain policy objectives and policy action to the broader public. This requires a constant process of translation of different languages. This translation cannot rely on an established dictionary. Videos, barrier-free-language, listening events and policy panels are all part of the tools that we should use to assist that translation. We also need to invest more time and effort into engaging with students of economics, finance, and other social sciences.

Good communication is particularly important in the field of financial stability. Macroprudential policy aims at building up resilience and is of a preventive nature. It needs to act prior to the build-up of vulnerabilities and risks to financial stability. Therefore, it is hard to observe its effectiveness: if the financial system continues to function well, this could be due to good luck or good policy. The outcome would be observationally equivalent.

Building trust in the ability of authorities to address risks to financial stability takes time. Financial sector reforms of the past decade have made the financial system more resilient. Whether risks have been pushed to other, less regulated parts of the financial system, and how the global financial system will weather the next storm, requires heightened attention.

5. References

Allen, Hillary J. (2022). Driverless Finance – Fintech's Impact on Financial Stability. Oxford University Press.

Arnold, Katrin, Rodolfo Dall’Orto Mas, Christian Fehlker, and Benjamin Vonessen. (2020): The Case for Central Bank Independence. ECB Occasional Paper Series. No. 248.

Barro, Robert, and David Gordon (1983). Rules, Discretion and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy. Journal of Monetary Economics. 12: 101-121.

Bayoumi, Tamim, Giovanni Dell'Ariccia, Karl F.Habermeier, Tommaso Mancini Griffoli, and Fabian Valencia. (2014): Monetary Policy in the New Normal, IMF Staff Discussion Notes, No. 14/3, April.

Blinder, Alan (2004). The Quiet Revolution: Central Banking Goes Modern. Yale University Press.

Brunnermeier, Markus K. (2016): Financial Dominance, XII. Paolo Baffi Lecture, Banca D’Italia.

Brunnermeier, Markus K. (2021). The Resilient Society: Lessons from the pandemic for recovering from the next major shock. Endeavor Literary Press

Buch, Claudia M. (2021a). Central Bank Independence: Mandates, Mechanisms, and Modifications. Remarks prepared for the panel discussion “Lessons from Central Bank History?” on the occasion of the conference “From Reichsbank to Bundesbank”. Frankfurt a.M.

Buch, Claudia M. (2021b). Bank Resolution: Delivering for Financial Stability Session II: Achieving a Home-Host Balance. Introductory statement SRB Annual Conference 2021. Frankfurt a.M.

Buch, Claudia M., and Benjamin Weigert (2021). Climate Change and Financial Stability: Contributions to the Debate. https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/869058/f33e5c6b7081fe801dc663205f7feee9/mL/paper-buch-weigert-data.pdf

Buch, Claudia M., Edgar Vogel, and Benjamin Weigert (2018). Evaluating Macroprudential Policies. ESRB: Working Paper No. 2018/76. Frankfurt a.M.

Buchheim, Christoph (2001). Die Unabhängigkeit der Bundesbank: Folge eines amerikanischen Oktrois? Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 49(1): 1-30.

Buiter, Willem H. (2014): Central Banks: Powerful, Political and Unaccountable?. CEPR Discussion Paper. No. 10223.

Calvo, Guillermo A. (1978): On the Time Consistency of Optimal Policy in a Monetary Economy. Econometrica, 46 (6). 1411-1428.

Cukierman, Alex, Steven B. Webb, and Bilin Neyapti (1992): Measuring the Independence of Central Banks and its Effect on Policy Outcomes. World Bank Economic Review, 6 (3), 353-398.

Deaton, Angus (2022). Is Economic Failure an Economics Failure?. Project Syndicate Quarterly: The year ahead 2023. P. 43-45

Deutsche Bundesbank (2019). Financial Cycles in the Euro Area. Monthly report. P. 51-74. Frankfurt a.M.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2022). Finanzstabilitätsbericht 2022. Frankfurt a.M.

Edge, Rochelle M., and J. Nellie Liang (2020). Financial Stability Governance and Basel III Macroprudential Capital Buffers. Hutchins Center Working Paper 56. Brookings. Washington DC.

European Commission (2022). Eurobarometer: Key Challenges of our Times – Autumn 2022. Special Eurobarometer 531 Autumn 2022. Summary Fieldwork: October-November 2022. Link: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2892.

European Central Bank (2022). Financial Stability Review. November 2022. Frankfurt a.M.

European Systemic Risk Board (2022). Warning on Vulnerabilities in the EU Financial System. September 2022. Frankfurt a.M.

Farhi, Emmanuel, and Jean Tirole (2009): Leverage and the Central Banker’s Put. American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings). 99 (2): 589-593.

Farhi, Emmanuel, and Jean Tirole (2012): Collective Moral Hazard, Maturity Mismatch and Systemic Bailouts. American Economic Review. 102(1): 60-93.

Financial Stability Board (2017). Framework for Post-Implementation Evaluation of the Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms. Basel.

Goodhart, Charles, and Manoj Pradhan (2020). The Great Demographic Reversal – Aging Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hellwig, Martin (1998). Systemische Risiken im Finanzsektor. Schriften des Vereins für Socialpolitik NF 261. Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften Beiheft 7: 123-151.

Houben, Aerdt, Remco van der Molen, and Peter Wierts (2012). Making Macroprudential Policy Operational. Revue de Stabilité financière. Luxemburg.

Kay, John, and Mervyn King (2020). Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers. N.N. Norton.

Kydland, Finn E., and Edward C. Prescott (1977). Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans. Journal of Political Economy 85: 473-492.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff (2009). This Time is Different: Eight centuries of financial folly. Princeton University Press. Princeton.

Reis, Ricardo (2022a). What Can Keep Euro Area Inflation High?. Paper prepared for the 76th Economic Policy Panel Meeting, October 2022, Berlin.

Reis, Ricardo (2022b). The Burst of High Inflation in 2021-22: How and Why Did We Get Here?. BIS Working Paper No 1060.

Romelli, Davide (2022). The Political Economy of Reforms in Central Bank Design: Evidence from a New Dataset. Economic Policy. Forthcoming.

Shiller, Robert J. (2019). Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events. Princeton University Press.

Sims, Christopher A. (1999): The Precarious Fiscal Foundations of EMU, De Economist, 147, 415-436.

Sims, Christopher A. (2001): Fiscal Aspects of Central Bank Independence, CESIfo Working Paper No 547.

Tucker, Paul (2018). Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy and the Regulatory State. Princeton University Press.

Véron, Nicolas (2022). The First Decade of Europe’s Banking Union: Much Achieved, Much Still to Do. Mimeo.

Footnotes:

- I would like to thank Sandra Eickmeier, Christof Freimuth, and Phillip König for most helpful comments and inputs to an earlier draft. All remaining errors and inconsistencies are my own.

- I borrow this term from Reis (2022b: 14) who argues that, after two decades of low inflation, the public did not pay much attention to central banks, trusting that inflation would remain low also in the future.

- Part of the following discussion draws on a speech given in September 2021 on central bank independence, see Buch (2021a).

- Seehttps://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Inflation_in_the_euro_area

- See European Commission (2022: 8).

- Generally, de jure independence of central banks has increased over time (Cukierman et al. 1992, Romelli 2022). Reis (2022b) identifies three elements of an institutional framework contributing to price stability: (i) independence from the Ministry of Finance, (ii) narrow mandates, transparency, and measurable performance, and (iii) interest rates as the main policy tool.

- For example, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has an explicit quantitative objective of a 2% inflation rate. In the Eurosystem there is some leeway in terms of interpreting the qualitative goal of “maintaining price stability” quantitatively.

- See Kydland and Prescott (1977), Calvo (1978), or Barro and Gordon (1983).

- The role of central banks in addressing climate change is an additional discussion which challenges the traditional role of central banks and their relation to fiscal policy. See Buch and Weigert (2021) for a discussion.

- See https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2022/html/ecb.mp221215~f3461d7b6e.en.html https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2022/html/ecb.mp221215~f3461d7b6e.en.html.

- See ECB (2022) and ESRB (2022).

- See Deutsche Bundesbank (2022).

- See Buch (2021b) and Véron (2022).

- See https://www.bundesbank.de/content/618304/

- See 4th Act amending the Bundesbank Act, dating from 1992, https://dserver.bundestag.de/brd/1992/D400+92.pdf

- See 5th and 6th Act amending the Bundesbank Act, dating from 1994 and 1997, https://www.bundesbank.de/content/671676

- Buchheim (2001) documents the discussion on the respective legislation, showing the importance of the US position in favour of an independent central bank. German authorities have, to the contrary, favoured a less independent central bank initially. By the time of the passage of the Bundesbank Act though, he argues that there was strong public support for an independent central bank.

- Both, central bank independence as well as the primary objective of the European Central Bank’s monetary policy are enshrined in the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union. See also https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/orga/independence/html/index.en.html.

- See Arnold et al. (2020), Bayoumi et al. (2014), or Tucker (2018).

- For a discussion on the features of financial cycles, see Deutsche Bundesbank (2019).

- See https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/search/review/html/price-stability-objective.en.html.

- See Edge and Lliang (2020) for an analysis on the governance structure of macroprudential policy, including the role of central banks, in the context of decisions on the countercyclical capital buffer.

- See Buch, Vogel and Weigert (2018) for a description of the policy cycle linking policy objectives, indicators, and policy evaluation. Houben, van der Molen, and Wierts (2012) develop a similar structure in the context of macroprudential policy.

- For a discussion of decision-making in times of radical uncertainties, see Kay and King (2020).

- See Shiller (2019).

- See Brunnermeier (2021).

- This can include experts from other professions such as sociology or philosophy (Deaton 2022).

- For details on the ECB strategy review see https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/search/review/html/index.en.html.

- See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TdlYUfTudhE.