The ECB Governing Council adopted a new monetary policy instrument on 21 July 2022: the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), a toolkit addition designed to safeguard (monetary policy) transmission. It is intended, in particular, to ensure the smooth transmission of monetary policy as the process of normalising monetary policy continues. This is a precondition for the Eurosystem, i.e. the European Central Bank (ECB) and the national central banks of the euro area Member States, to be able to deliver on its mandate of maintaining price stability.

The price stability objective It is the responsibility of the Eurosystem – i.e. the ECB and the national central banks of the euro area Member States – to maintain price stability in the euro area. The ECB Governing Council, of which the Bundesbank President is also a member, considers that price stability is best maintained by aiming for a 2% inflation rate over the medium term. |

-

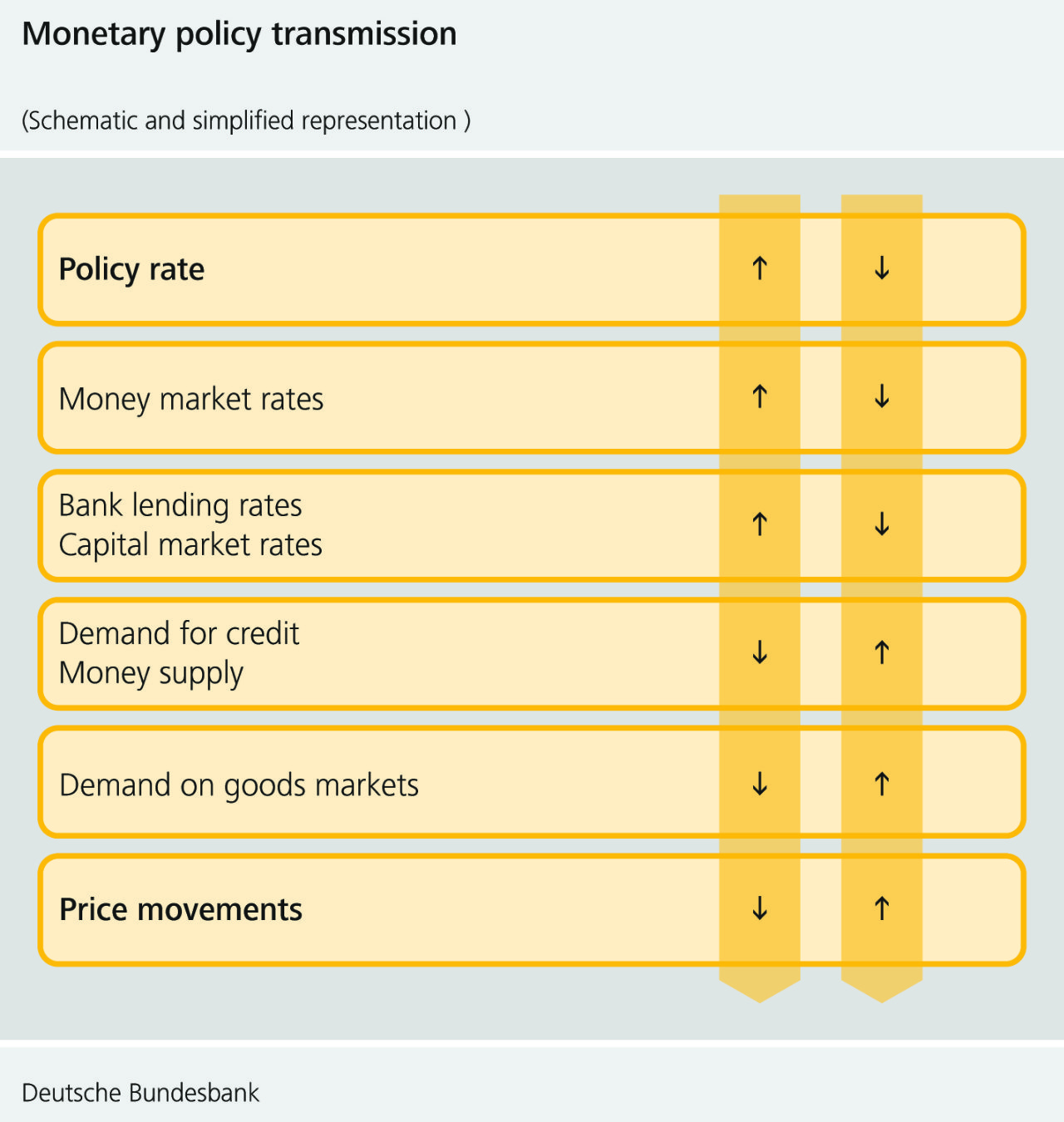

“Monetary policy transmission” refers to the process through which monetary policy settings ultimately flow through to prices. The central banks first affect interest rates. By changing their policy rates, they influence short-term market interest rates, which in turn has a knock-on effect on longer-term interest rates. In principle, central banks can also influence longer-term interest rates more directly, for example by buying and selling bonds. However, policy rates are generally the main monetary policy instrument.

On 21 July 2022, after a protracted period of particularly low interest rates, the ECB Governing Council decided, in a first step, to raise its three key interest rates by 0.5 percentage point each. This was intended to normalise monetary policy and thus combat the current high inflation rate. At its subsequent meeting on 8 September 2022, the Governing Council took an even more significant step, raising key interest rates by 0.75 percentage point. If key interest rates rise, market interest rates also tend to rise; in other words, the monetary policy stimulus is passed on. Higher market interest rates, in turn, lead to households consuming less and firms investing less than they would at lower interest rates, thus dampening economic growth. As a result of lower demand, firms subsequently adjust their prices downwards. This ultimately weakens price pressures.

The Governing Council is responsible for price stability in the euro area as a whole. It aims to achieve an inflation rate of 2% over the medium term. But even if the inflation rate for the euro area as a whole is 2%, inflation rates in individual Member States may vary. This may be due, for example, to the fact that the euro area Member States have different economic structures or are in different phases of the business cycle.

Market rates may also differ between euro area Member States. Although the key interest rates are the same for all countries, interest rates on government bonds, for example, may vary. For instance, there may be what are known as risk premia on interest rates, above all when there are doubts on the capital market regarding the soundness of individual countries’ government finances. Potential reasons underlying such doubts include high government debt, structural growth problems or uncertain political prospects in a Member State. In the euro area, it is the responsibility of each Member State to ensure its own sound public finances and sustainable economic structures, and to assure the capital markets of these. There are also common fiscal solidarity mechanisms in place to assist individual Member States experiencing financial problems. These include, for example, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). However, the European Treaties prohibit the Eurosystem from providing monetary financing to the Member States. This means, amongst other things, that the ECB Governing Council is not responsible for aligning interest rate levels in the Member States.

Differing financing conditions in the individual euro area Member States are therefore usually the result of normal market activity, reflecting the specific macroeconomic and fiscal policy conditions in the individual Member States. Interest rate developments in the individual Member States may also differ from one another in the course of a normalisation of monetary policy. A key interest rate hike, for instance, makes relatively risk-free bonds more attractive to investors. At the same time, investors demand greater compensation for riskier bonds in the form of higher interest rates. Accordingly, government bond yields in Member States with high levels of government debt tend to rise more strongly when key interest rates are raised than, for example, in Member States with lower levels of debt.

However, it cannot be ruled out that self-reinforcing, destabilising undesirable developments will occur in the financial markets – for example, in course of the ECB’s monetary policy normalisation. As a result, government, corporate or household bond yields may rise excessively and move away from fundamentals. Ultimately, there is, amongst other things, the risk of this giving rise to a self-fulfilling debt crisis.

Transmission mechanism of monetary policy

Traditionally, central banks ensure price stability by adjusting their policy rates. This simplified depiction of the transmission mechanism illustrates how a policy rate change usually affects price developments.

The starting point of the monetary policy chain presented here – the interest rate channel – is the interest rate set by the central bank at which banks can borrow money from the central bank. If the central bank raises its policy rates, the general short-term interest rate normally increases as well. Banks usually pass on the increased short-term interest rate to their customers by raising their interest rates on corporate and personal loans. The longer-term interest rate level also rises. When bank loans become more expensive, demand for such loans generally declines. As a result, credit-financed demand for goods and services in the economy weakens. In such an environment, enterprises have, amongst other things, less scope to push through price increases. Consequently, aggregate inflation is dampened and the inflation rate declines. The opposite holds true if the central bank lowers its policy rates: it becomes cheaper for enterprises and households to take out bank loans, which in turn drives enterprises to borrow in order to finance their investment activity and, at the same time, boosts consumers’ demand for durable consumer goods. Aggregate demand rises. Enterprises can raise their prices both more easily and by a greater amount. The rate of inflation tends to rise.

Further information

-

The TPI can be activated if the ECB Governing Council finds that there are unwarranted, disorderly market developments that are disrupting monetary policy transmission and thus impairing the Eurosystem’s ability to maintain price stability. In such a case, the Eurosystem central banks could, under certain conditions, purchase securities from individual Member States.

TPI purchases would be focused on public sector securities, which may only be made on the secondary market – i.e. in the market for bonds that are already in circulation. Such purchases would reduce the risk premia on these securities. This could dampen interest rate movements in the sovereign bond market, which in turn could improve financing conditions for households and enterprises. The fundamentally unwarranted interest rate levels addressed by the TPI would be corrected, bringing financing conditions in the Member States concerned back more closely in line with fundamental economic and political conditions and reducing fragmentation in the euro area. Monetary policy settings could then better flow through to prices.

-

In any TPI use case, the conditions that must be met in order for the instrument to be activated first need to be specified. The purpose of these conditions is to ensure that the TPI complies with the Eurosystem’s mandate, that its use is proportionate, and that it does not violate the prohibition of monetary financing of government. Accordingly, activation of the TPI must be based on a comprehensive assessment by the ECB Governing Council of (its proportionality to) specific circumstances on a case-by-case basis. In addition, the Governing Council has decided that Member States whose bonds are to be purchased under the TPI must fulfil fiscal and macroeconomic policy prerequisites. “In this context, we have made it clear that we would activate the instrument only once a number of criteria have been fulfilled,” Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel told the “Rheinische Post” newspaper in August. “It still holds entirely true that governments are responsible for their budgetary and fiscal policies. So, if national budgetary and fiscal policies cause interest rate premia to rise, this is not a case for the TPI.”

The Governing Council decides on the specific conditions and whether or not they have been met in the comprehensive overall assessment carried out prior to any activation of the TPI in response to a specific situation. This is intended to ensure that Member States whose bonds may be purchased are pursuing sound and sustainable financial and macroeconomic policies. The TPI decision identifies four criteria that could be of particular importance in this connection (see the box). In addition, the scale of possible TPI purchases depends on the severity of the risks facing monetary policy transmission. Ultimately, bonds would only be purchased on a temporary basis. Purchases would then be terminated by the Governing Council either if a durable improvement in transmission becomes apparent or if, after a certain period of time, the Governing Council concludes that interest rates no longer stand in clear contrast to country-specific fundamentals.

The Governing Council has established a list of criteria to assess whether the Member State in which the Eurosystem may conduct purchases under the TPI is pursuing sound and sustainable fiscal and macroeconomic policies. These criteria will be an input into the Governing Council’s decision-making and will be dynamically adjusted to the unfolding risks and conditions to be addressed. In particular, the criteria considered include:

- Fiscal rules. The Member State is not subject to an excessive deficit procedure (EDP), nor has it been assessed as having failed to take effective action in response to an EU Council recommendation under Article 126(7) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

- Macroeconomic imbalances. The Member State is not subject to an excessive imbalance procedure (EIP), nor has it been assessed as having failed to take the recommended corrective action related to an EU Council recommendation under Article 121(4) TFEU.

- Fiscal sustainability. In ascertaining that the trajectory of public debt is sustainable, the Governing Council will take into account, where available, the debt sustainability analyses conducted by the European Commission, the European Stability Mechanism, the International Monetary Fund and other institutions, together with the ECB’s internal analysis.

- Sound and sustainable macroeconomic policies. The Member State complies with the commitments submitted in the recovery and resilience plans (RRPs) for the Recovery and Resilience Facility and with the European Commission’s country-specific recommendations in the fiscal sphere under the European Semester.